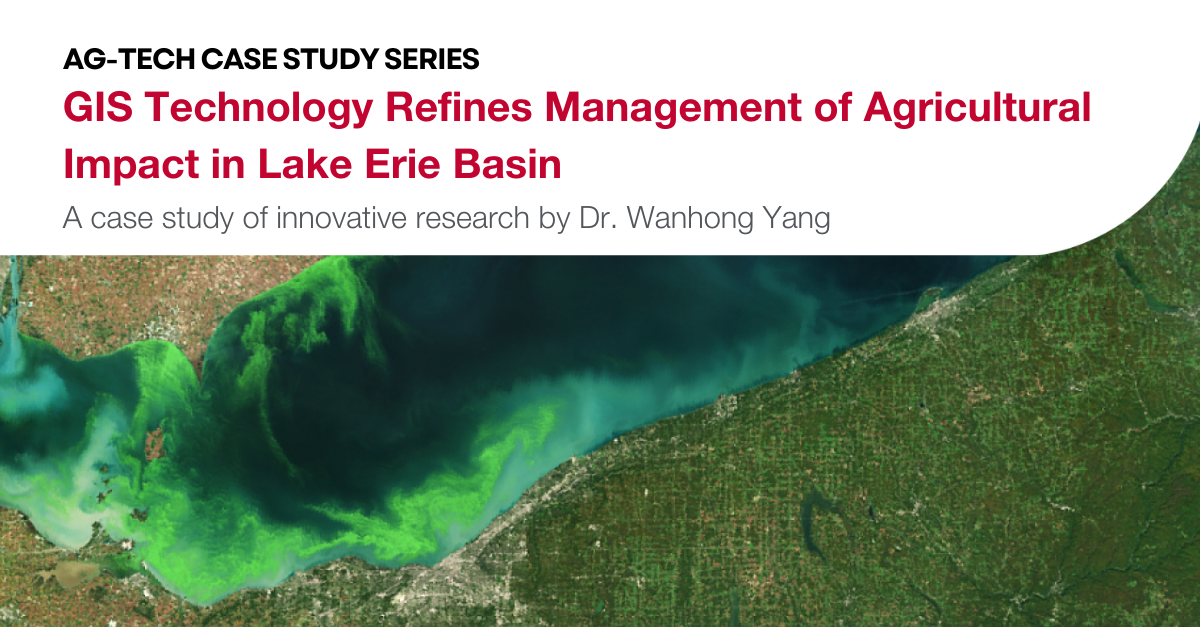

Along the sandy, windswept shores of Lake Erie, the impact of farming on Southern Ontario’s agricultural watersheds is a pressing concern and a major focus of conservation efforts and water quality strategies. Blue-green algae chokes up huge portions of Lake Erie every year, contaminating the water that hundreds of thousands of people rely on for drinking, cooking, and bathing.

As these toxic algae blooms increase in size and severity, conservation authorities and farmers are looking for ways to manage fertilizer runoff from farm fields, a major source of the nitrogen and phosphorus that feed the algae, while still maintaining agricultural productivity. There is abundant regional data about the impact of agriculture on water quality, but until recently, farmers had little to no access to local, site-specific data that could inform practical decisions to reduce their operations’ environmental impact.

This is beginning to change, thanks to multidisciplinary research led by Dr. Wanhong Yang, Professor of Geography at the University of Guelph, and funded over many years by Food from Thought, Environment and Climate Change Canada, ALUS Canada, and the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance, a collaboration between the Government of Ontario and the University of Guelph.

Yang and a research team that includes co-investigators Dr. Eric Nost and Dr. Diana Lewis will use computer models to identify hot spots for agricultural impacts, evaluate risks at the local level, and guide conservation efforts in high-priority locations. This research builds on over 20 years of Yang’s Geographical Information System (GIS)-based research, through which his team developed Integrated Modelling for Watershed Evaluation of Beneficial Management Practices, a computer model better known as IMWEBs.

The IMWEBS tool is accessible through an online platform with a scope of the entire Lake Erie Basin, an area that includes 21,750 square kilometres of rich, biologically diverse land stretching from Windsor to Guelph, including agricultural centres near London, Kitchener, and Sarnia, and within Chatham-Kent. The tool will allow users to compare the cost and environmental impact of different beneficial management practices using site-specific data that lets farmers develop concrete strategies to reduce their individual impacts and understand the financial effects of those decisions.

“We simply want to provide local actors with the scientific data they need to make prudent decisions. This will eliminate much of the guesswork involved in conservation efforts, and we believe it will benefit everyone in the agriculture and conservation communities.” – Dr. Wanhong Yang

The current project has three phases, starting with the collection of climate, topography, soil, land use, land management, and water monitoring data from the Lake Erie Basin. Then, researchers will use IMWEBs to simulate how water, sediment, and nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorous) move from agricultural fields into streams and, ultimately, into Lake Erie. IMWEBs will also use observed data from conservation authorities to calibrate and validate the computer simulations and ensure the models reflect accurate, real-world conditions in the Lake Erie basin.

In the project’s final stage, the computer model will identify agricultural “hot-spots” — areas where there are high volumes of nutrients entering watercourses. The identified hot-spots can then use predictive field-level data to develop land management best practices that will reduce agricultural run-off. With this data-driven approach, conservation authorities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can work alongside farmers to achieve more sustainable operations.

“Agents can come and say, ‘This is just a naturally more sensitive area. Let’s work on it,’” said Yang. “That’s how the information will be used in the future.”

By identifying hot-spots within their operations, farmers can also be careful and precise when investing in water quality improvement strategies. These may include planting tree buffers, reducing nutrient application to fields, and implementing conservation tillage practices.

Giving priority to the hot-spots identified through this system will ultimately save costs for farmers by focusing their efforts. Yang explains, “It’s just like when we do a repair [on a car or a house]. We only repair a certain location.”

A key goal is to enable targeted conservation practices that make good business sense. This will help farmers build thriving agri-businesses that are environmentally sustainable. Already, this research is paying off in meaningful ways. In an early case study, Yang and his team applied IMWEBs computer models to the Catfish Creek watershed in Elgin and Oxford counties. The watershed has a drainage area of about 39,000 hectares, of which 85% is agricultural land.

The average total phosphorus export from those fields is about 1.4 kilograms per hectare per year; but a small number of fields showed phosphorous exports at double this rate. Those high-volume areas — comprising only 4,500 hectares, or 14% of all agricultural land in the watershed — have been identified as hot-spots and areas of focus for conservation.

Indigenous engagement and consultation with other stakeholders are another key element of this project, and once completed, this would be one of the first online GIS tools of its kind in Canada. It would be the first such project to focus on the entire Lake Erie Basin, and its intent is to inspire data-driven collaboration among stakeholders.

“We simply want to provide local actors with the scientific data they need to make prudent decisions,” said Yang. “This will eliminate much of the guesswork involved in conservation efforts, and we believe it will benefit everyone in the agriculture and conservation communities.”